Blog

The Heroes in Headsets

June 08, 2022

Emergency dispatchers, 9-1-1 call takers, operators, emergency telecommunicators…they are the force which connects responders to the emergency caller. A vital link in emergency response, coordinating communications between the caller and police officers, firefighters, and paramedics ensuring safe, swift, and appropriate responses.

Emergency medical dispatch has evolved over the last 50 years from a system initially designed to limit abuse of the emergency medical services (EMS) to an integral part of EMS response. Its goal?

“To send the right thing, to the right person, at the right time, in the right way, and to say the right thing until help arrives.”

But when did it all start?

Specialized care and transportation of the acutely ill and injured goes back at least as far as the Napoleonic war, starting with Pierre François Percy and Dominique-Jean Larrey.

Percy the son of a surgeon, entered the medical service in 1776. During the French Revolution, in 1792, he became a consultant surgeon to the Army of the North where he invented the "wurst" wagon, a padded wagon designed to transport medical staff and supplies to the front for immediate wound treatment. Almost simultaneously, Larrey started creating an ambulance service to transport wounded soldiers away from the battlefield. Percy’s invention never achieved the widespread success of Larrey's ambulance, but both inventions signified the beginning of something revolutionary (no pun intended) …the beginning of the EMS service we know, love, and appreciate today.

The Emergency dispatcher-type role we are familiar with began only as recently as the 1970’s in the US. A paramedic named Bill Tune from Phoenix, Arizona, was conveniently present at a 9-1-1 dispatch center, and provided unplanned and unscripted pre-arrival instructions to a mother calling for her nonbreathing baby. The child survived, and the then Fire Chief, instructed the center to begin routinely offering these prearrival instructions. The program was referred to as “medical self help”.

By 1976, a doctoral thesis on “paramedic unit placement” started raising questions concerning EMS abuse and the role of dispatch in preventing it. In 1977, Dr Jeff Clawson, now regarded as the pioneer behind Emergency Medical Dispatch began to develop protocols for dispatchers. The protocols were known as “Medical Priority Dispatching” and were introduced into Salt Lake City’s Fire Department in 1978. There were 3 essential components to Clawson's protocols:

- Interrogation questions, aka “key questions”

- Telephone help, aka “prearrival instructions”

- Response determinants aka “level of response”, incl type of warning lights and/or sirens used.

These instructions eventually transitioned into the MPDS “Medical Priority Dispatching System” the industry uses today.

Personal Skills and Challenges

Highly trained and professional, emergency call takers are communications specialists and the ultimate multi-taskers…with their desks bearing a striking resemblance to NASA’s mission control with solid language skills and honed interview techniques they need to acquire the right information from each emergency call. Master tacticians with sound technological and directional knowledge they also require a variety of soft skills to perform their jobs effectively. It’s important they’re great listeners, have clear judgement, are well-organized, compassionate and patient.

Highly trained and professional, emergency call takers are communications specialists and the ultimate multi-taskers…with their desks bearing a striking resemblance to NASA’s mission control with solid language skills and honed interview techniques they need to acquire the right information from each emergency call. Master tacticians with sound technological and directional knowledge they also require a variety of soft skills to perform their jobs effectively. It’s important they’re great listeners, have clear judgement, are well-organized, compassionate and patient.

This job is challenging, with long hours (sometimes 24-hour shifts). It’s highly stressful handling phone calls from people who are having, in many cases, the worst day of their life, and it’s not uncommon for them to bear the brunt of verbal abuse, or to suffer PTSD as a consequence of dealing with adrenaline-pumped and tragic calls day in and day out. Emotional control, a calm demeanour and the ability the “move on” once a call has ended are crucial skills, but the job can chip away at mental health over time, and sadly these telecommunicators are just as likely to suffer from mental health challenges as any other First Responder:

"You kind of try to put it away just to kind of protect yourself because the next call is going to happen," she said. "It can really play on your mind. You get through your shift, and you get home, and it doesn't go away. It's still there. Depending on how traumatic the call was, and how you absorbed it, could play on your mind for months and years … as an operational-stress injury where it becomes a post-traumatic event." – CBC News

Fighting for Industry Recognition and staffing shortages

The definition of a first responder is “someone designated or trained to respond to an emergency, yet a disagreement centred around whether 9-1-1 telecommunicators are indeed “first responders” is still ongoing, despite APCO recommending the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) be revised as far back as 2014.

Reclassification of the SOC would see a dispatcher’s status go from “Administrative Support” (same as telephone operator or office admin), to “Protective” (such as a firefighter). Unfortunately, such recognition hasn’t been given…yet. As of April 2021, the "Supporting Accurate Views of Emergency Services Act" (911 SAVES Act) was introduced to the US Senate accompanying rationale that telecommunicators are essentially the “first of the first responders”. All eyes are watching whether this will be passed, since a similar bill was attempted in 2019 and failed…

This is not only sad, but unjust. Office administrators don’t help save lives on a daily basis. And what’s even more disconcerting is staffing shortages at emergency communication centers (ECC’s) are directly linked to this failure, making it impossible for any justifications to, wage improvement, work environment or training. Consequentially, those considering a career in an ECC often view the role as low wage, with zero upward career mobility. It’s also predicted that due to upcoming retirements there will be over 10,000 jobs to fill in the not-to-distant future, and not enough people willing to fill them.

The Technology

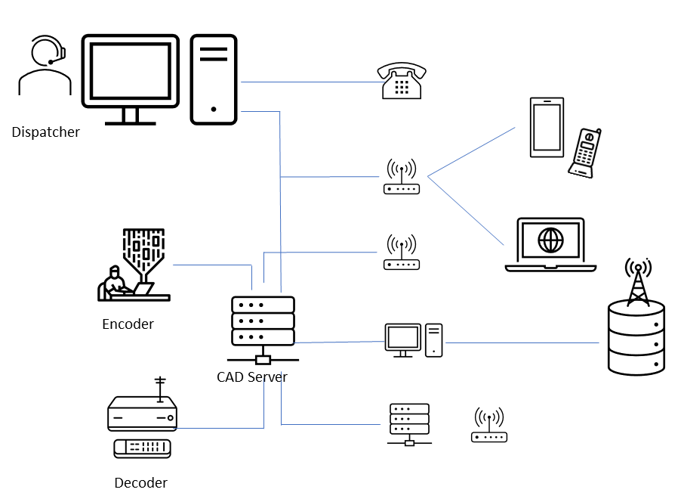

Dispatchers, call takers, and operators use a system called Computer-aided dispatch (CAD) to prioritize and record incident calls, identify the location and status of responders out in the field, and effectually dispatch emergency resources and personnel. Responders can also receive messages from the same CAD system via their own mobile data terminals (MDTs), radios, and even cell phones.

Simplified CAD system

Simplified CAD system

CAD systems are capable of interfacing with GIS (geographic information system), automatic vehicle location (AVL) systems, caller identification (ID) systems and various other databases. Plus unified CADs (UCAD) interface with multiple agencies and/or computer systems serving law enforcement, fire, and EMS.

But it’s not all as technology forward as you would think or hope. Many emergency call centers across the US and Canada and Europe, due to underfunding, are still working with end-of-life legacy systems and are no where near ready to upgrade to a Next Generation System any time soon.

How the right tools can help

The first question you’re asked from a 9-1-1 call taker is:

“WHERE IS YOUR EMERGENCY”

Yet contrary to public perception 9-1-1 doesn’t automatically know where you are in many cases, especially for indoor calls and multi-level dwellings like apartment blocks. If they can’t find you they can’t help you, and trying to decipher a caller’s location due to uncertainty or inability to verbalize means time gets wasted…and time isn’t in abundance when you’re having a heart attack.

E9-1-1 and NG9-1-1 use the same location methodologies to try an pinpoint a call: GPS, Wi-Fi, and cell tower/triangulation plus supplemental data provided on a “best-effort” basis. Estimated search areas for mobile location slow down call routing and a Dispatcher’s ability to handle and dispatch help, this leads to substantially more stress for everyone involved and in over 10,000 US cases each year, death of the caller.

Provisioning Dispatchable Address, “The street address of the caller, and additional information, such as room or floor number” would alleviate some of stress which impacts call takers each day, it’s fair to say it would streamline the MPDS, offering faster arrivals to emergency scenes, and could help save thousands of lives each year. But don’t just take our word for it. In 2020 ELi Technology, alongside IBM, had the privilege of hosting a Design Thinking workshop with a leading112 Operator in Europe.

In essence, the workshop analyzed what “value” accurate localization brings to the delivery chain of an emergency call: beginning with the caller and ending in the first responder, with dispatchers obviously being front and center.

The overriding and collective consensus was that providing dispatchable address, would mean:

- reductions in call handling times of 30-90 seconds per call,

- efficient utilization of resources,

- stress reduction for callers and call takers,

- leading to more lives saved and a dramatically more efficient ESN system.

Sounds like something we should be thinking more about…

Sources:

- https://www.rd.com/list/secrets-911-dispatcher-wont-tell-you/

- https://cdn.emergencydispatch.org/iaed/pdf/SS13_EMD_in_USA_a_Historical_Perspective.pdf

- https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/CAD_TN_0911-508.pdf

- https://youtu.be/Qn9nM5mcIHw

- https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/emsworld/article/1223382/ems-hall-fame-pioneers-prehospital-care-clawson-cowley

- https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/911-calls-operators-dispatchers-mental-health-1.5798960

- https://www.nena.org/page/reclassification_map#texas

- https://www.police1.com/police-products/police-technology/publicsafetysoftware/articles/why-911-dispatchers-should-be-considered-first-responders-V0H4cmLgYnP47ntK/

- https://www.rrmediagroup.com/Features/FeaturesDetails/FID/1100

- https://www.ems1.com/legislation-funding/articles/house-passes-bill-to-reclassify-911-dispatchers-as-protective-service-occupations-6tqdaV2uYpc8OFrg/